Post By : 2025-05-23T23:05:07"

How gardening can help you live better for longer"

Marianne Rogstad, a retired grandmother from Norway, is a lifelong learner. She worked as a hotel clerk in Switzerland for five decades, where she spent her days immersed in new languages and cultures.

But when Rogstad returned to Norway, she was diagnosed with dementia. She soon became isolated and lost those sources of stimulation. That was until she joined Impulssenter – a small "care farm" outside of Oslo. The care farm borrows its name from the way it serves people's impulses to work and connect with others, says Henreitte Bringsjord, whose parents founded the farm.

"My mum and dad loved farm work, and they thought about how hard it is for people with dementia to stop working and lose their social life. So, they wanted to help people with dementia become a part of life again," says Bringsjord, who now co-manages the farm.

In 2015, Norway became one of the first countries to create a national dementia care plan, which includes government-offered daycare services such as Inn på tunet – translated as "into the yard" – or care farms. Now, as researchers recognise the vast cognitive benefits of working on the land, more communities are integrating gardening into healthcare – treating all kinds of health needs through socially-prescribed activities in nature, or green prescriptions.

"Nature prescriptions can increase physical activity and social connection while reducing stress, which have multiple positive knock-on effects for blood pressure, blood sugar control and healthy weight, reducing the risk of diseases that can lead to dementia," says Melissa Lem, a family physician based in Vancouver and researcher at the University of British Columbia, Canada – where she examines the opportunities and barriers around nature-based prescriptions. "We all know that more physical activity improves mental and physical health, but gardening supercharges those benefits," she says.

New data sheds light on the advantages of spending time gardening. In a first-of-its-kind study, researchers from the University of Edinburgh investigated if there might be a link between gardening and changes in intelligence our lifetimes. The study compared the intelligence test scores of participants at age 11 and age 79. The results showed those who spent time gardening showed greater lifetime improvement in their cognitive ability than those who never or rarely did.

"Engaging in gardening projects, learning about plants and general garden upkeep involves complex cognitive processes such as memory and executive function," said Janie Corley, the study's lead researcher, in a press release.

Nature provides soft fascination that reduces fatigue and irritability – Melissa Lem

Corley says some of those benefits may come from the "use it or lose it" cognitive framework, a theory that suggests the strength of our mental abilities in older adulthood depend on how frequently we use them. When we neglect to perform tasks that stimulate certain parts of our brain, those parts of our brain begin to lose their functionality, but regularly engaging in these activities – such as problem solving, learning a new skill or being creative – in older adulthood can have the opposite effect.

One 2002 study of more than 800 nuns in the United States found that frequently participating in cognitively stimulating activities reduced their risk of Alzheimer's disease. A more recent study of older adults in Japan found participation in meaningful activities could protect against declines in memory function. Meanwhile, other research has found that people who received an intervention of cognitively stimulating activities, typically in a social setting, saw improvements in cognition, mood, communication and social interaction.

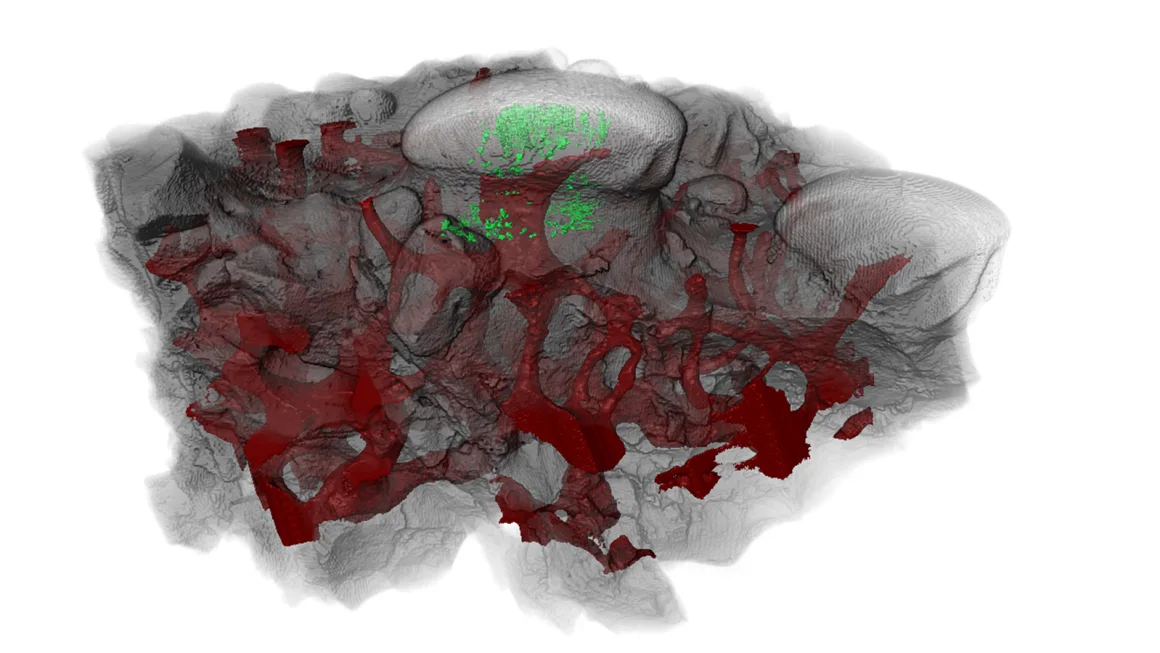

And gardening appears to have specific cognitive benefits. For one thing, gardeners seem to experience gains in the nerve levels of brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF), a protein that plays an important role in the growth and survival of neurons. They also receive boosts to their vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF), a protein associated with improving cognitive functioning.

One 2006 study from the University of New South Wales, which followed Australian men and women throughout their sixties, found that those who gardened on a daily basis had a 36% lower risk of developing dementia than those who didn't. Gardening has also been shown to improve attention, lessen stress, reduce falls and lower reliance on medications.

Some of these cognitive benefits may come from simply being in nature. Roger Ulrich, a world expert in designing health systems and a professor of architecture at Chalmers University in Sweden, was among the first to connect nature exposure to stress reduction. Throughout the 1980s and 1990s, he conducted a series of landmark studies demonstrating how simply looking at trees and other plants – even through a window – can reduce pain, boost positive emotions and strengthen concentration.

Ulrich suggested that these responses were driven by evolution. Since the ability to recover from a stressful situation was favourable for survival, the tendency to recover from stress in natural settings was genetically favourable, passed down through generations, and could explain why even just small doses of nature can improve wellbeing among modern humans.

"