.webp)

Post By : 2025-05-27"

‘Amazing’ reduction in Alzheimer’s risk verified by blood markers, study says"

When Penny Ashford’s father was diagnosed with early-stage Alzheimer’s disease at age 62, she knew the devastating brain disorder might one day steal her memory. In her late 50s, her free-floating anxiety turned to outright panic when she began struggling to find words.

“I couldn’t tell a story. I couldn’t get my words out,” said Ashford, now 61. “I remember sitting at a dinner party one time, and I couldn’t finish my thoughts. It was the most unbelievable moment.

“I came home and sobbed and told my husband, ‘Something is wrong with me. I can’t talk,’” she said. “I was petrified.”

Today, after a complete revamp of her lifestyle and overall health, Ashford’s struggles with retrieving words have eased, while measures of amyloid and tau proteins and neuroinflammation — all hallmark signs of Alzheimer’s — have fallen.

Ashford knows about these improvements because she’s part of a unique study tracking her progress via key blood biomarkers now being used to help diagnose early dementia. Instead of relying on painful spinal taps and expensive brain scans, these blood tests are heralded as a new, less invasive and time-consuming way to determine risk and aid in an earlier diagnosis of Alzheimer’s.

The preliminary data, presented Monday at the American Academy of Neurology annual meeting in San Diego, analyzed biomarkers on 54 participants in an ongoing preventive neurology study called the Biorepository Study for Neurodegenerative Diseases, or BioRAND.

“The field is primarily using various biomarkers to determine if you have dementia or not,” said lead study author Dr. Kellyann Niotis, a preventive neurologist who researches risk reduction for Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s diseases at the Institute for Neurodegenerative Diseases in Boca Raton, Florida.

“No one is really looking at the changes in these biomarkers as outcome measures, as a way of tracking progress in a person’s journey to improve their brain,” Niotis said. “We believe these biomarkers may show how the disease progression is being modified biologically by a person’s actions.”

Less invasive test for Alzheimer’s risk

Alzheimer’s blood tests are the key to widespread prevention of dementia, experts say. If people can be diagnosed in their doctor’s office, they can more immediately move into preventive care and implement lifestyle changes designed to slow the progression of their disease.

The problem, said senior study author Dr. Richard Isaacson, is the variability in how well these new blood biomarker tests work to predict or track disease progression.

“There is a dirty little secret in the Alzheimer’s blood testing community where so many testing platforms, biotech companies, and a flurry of new blood tests are released,” Isaacson said, “but it’s unclear which of these tests are most accurate to track progression and evaluate response to therapies to slow progression toward dementia.”

To address this gap, Isaacson’s research team and collaborators at five sites across the United States and Canada set forth to evaluate and eventually cross-compare the clinical use of what the neurologist said he believes will one day become “the cholesterol test for the brain.”

“In the not so far future, people in their 30s, 40s, 50s, 60s and beyond will get a baseline test to evaluate risk and help track progress over time — similar to how traditional cholesterol tests are used today,” said Isaacson, founder of one of the first Alzheimer’s prevention clinics in the United States.

“Our eventual goal is to offer a blood panel at cost to help democratize access and broaden the ability for people to receive care,” he added.

What Alzheimer’s blood tests currently measure

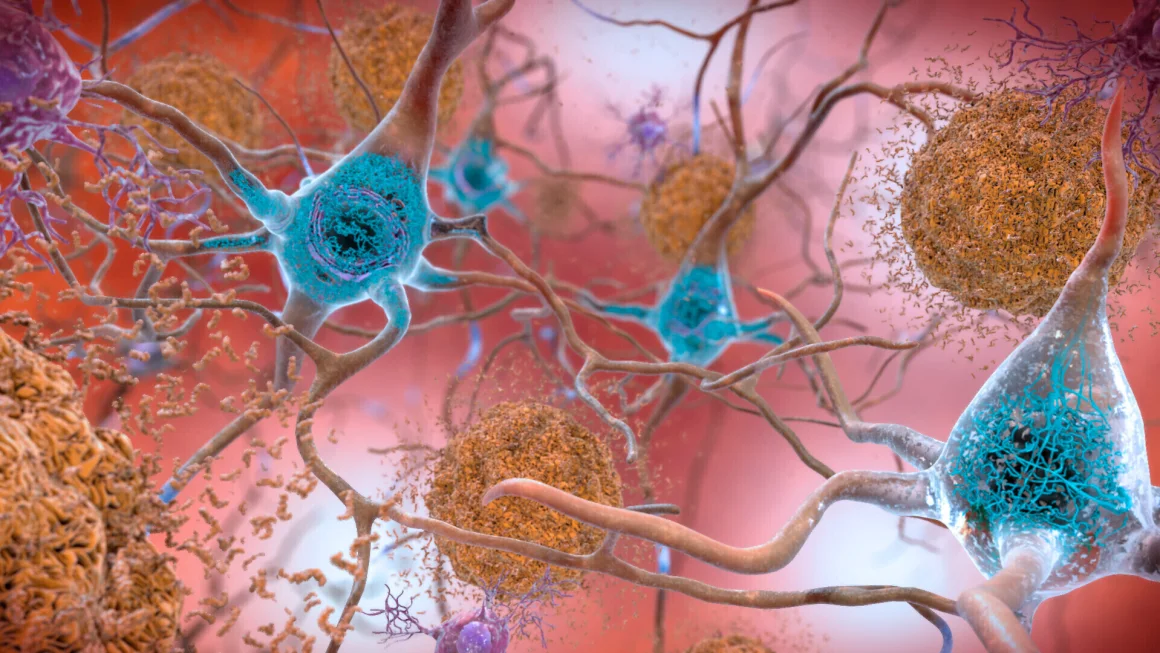

Measuring levels of both amyloid and tau is key to understanding and diagnosing Alzheimer’s and other forms of dementia.

Amyloid plaques play a key role in the development of Alzheimer’s when small clusters gather at synapses in the brain and interfere with the nerve cells’ ability to communicate. Such plaques are thought to trigger changes in tau proteins, which form into tangles in parts of the brain controlling memory.

Tau tangles are also implicated in other neurological diseases such as frontal lobe dementia, or FTD, and Lewy body dementia in which abnormal clumps of a protein called alpha-synuclein accumulate in the brain’s neurons.

The biomarker plasma phosphorylated tau 217, or p-tau217 for short, is a top contender in the diagnosis of mild cognitive impairment and early-stage Alzheimer’s disease. Its cousin, p-tau 181, is also a helpful indicator.

P-tau 217 is a “beautiful marker for Alzheimer’s,” Dr. Maria Carrillo, chief science officer of the Alzheimer’s Association, told CNN in an earlier interview.

“You’re not really measuring amyloid, but the test is telling you it’s there, and that’s been backed up with objective PET (positron emission tomography) scans that can see amyloid in the brain,” Carrillo said. “… If you have elevated tau in your brain, however, then we know that’s a sign of another type of dementia.”

Another biomarker test is the amyloid 42/40 ratio scan, which measures two types of amyloid proteins, another key biomarker of Alzheimer’s disease. At times, such tests work best when used together. In an earlier study, a combination of both amyloid and p-tau 217 tests, called the amyloid probability score, showed a 90% accuracy rate in determining whether memory loss is due to Alzheimer’s disease.

"